Tutorial: Physics Informed Neural Networks on PINA#

In this tutorial, we will demonstrate a typical use case of PINA on a toy problem, following the standard API procedure.

Specifically, the tutorial aims to introduce the following topics:

Explaining how to build PINA Problems,

Showing how to generate data for

PINNtraining

These are the two main steps needed before starting the modelling

optimization (choose model and solver, and train). We will show each

step in detail, and at the end, we will solve a simple Ordinary

Differential Equation (ODE) problem using the PINN solver.

Build a PINA problem#

Problem definition in the PINA framework is done by building a

python class, which inherits from one or more problem classes

(SpatialProblem, TimeDependentProblem, ParametricProblem, …)

depending on the nature of the problem. Below is an example:

Simple Ordinary Differential Equation#

Consider the following:

with the analytical solution \(u(x) = e^x\). In this case, our ODE

depends only on the spatial variable \(x\in(0,1)\) , meaning that

our Problem class is going to be inherited from the

SpatialProblem class:

from pina.problem import SpatialProblem

from pina.geometry import CartesianProblem

class SimpleODE(SpatialProblem):

output_variables = ['u']

spatial_domain = CartesianProblem({'x': [0, 1]})

# other stuff ...

Notice that we define output_variables as a list of symbols,

indicating the output variables of our equation (in this case only

\(u\)), this is done because in PINA the torch.Tensors are

labelled, allowing the user maximal flexibility for the manipulation of

the tensor. The spatial_domain variable indicates where the sample

points are going to be sampled in the domain, in this case

\(x\in[0,1]\).

What if our equation is also time-dependent? In this case, our class

will inherit from both SpatialProblem and TimeDependentProblem:

## routine needed to run the notebook on Google Colab

try:

import google.colab

IN_COLAB = True

except:

IN_COLAB = False

if IN_COLAB:

!pip install "pina-mathlab"

from pina.problem import SpatialProblem, TimeDependentProblem

from pina.geometry import CartesianDomain

class TimeSpaceODE(SpatialProblem, TimeDependentProblem):

output_variables = ['u']

spatial_domain = CartesianDomain({'x': [0, 1]})

temporal_domain = CartesianDomain({'t': [0, 1]})

# other stuff ...

where we have included the temporal_domain variable, indicating the

time domain wanted for the solution.

In summary, using PINA, we can initialize a problem with a class

which inherits from different base classes: SpatialProblem,

TimeDependentProblem, ParametricProblem, and so on depending on

the type of problem we are considering. Here are some examples (more on

the official documentation):

SpatialProblem\(\rightarrow\) a differential equation with spatial variable(s)spatial_domainTimeDependentProblem\(\rightarrow\) a time-dependent differential equation with temporal variable(s)temporal_domainParametricProblem\(\rightarrow\) a parametrized differential equation with parametric variable(s)parameter_domainAbstractProblem\(\rightarrow\) any PINA problem inherits from here

Write the problem class#

Once the Problem class is initialized, we need to represent the

differential equation in PINA. In order to do this, we need to load

the PINA operators from pina.operators module. Again, we’ll

consider Equation (1) and represent it in PINA:

from pina.problem import SpatialProblem

from pina.operators import grad

from pina import Condition

from pina.geometry import CartesianDomain

from pina.equation import Equation, FixedValue

import torch

class SimpleODE(SpatialProblem):

output_variables = ['u']

spatial_domain = CartesianDomain({'x': [0, 1]})

# defining the ode equation

def ode_equation(input_, output_):

# computing the derivative

u_x = grad(output_, input_, components=['u'], d=['x'])

# extracting the u input variable

u = output_.extract(['u'])

# calculate the residual and return it

return u_x - u

# conditions to hold

conditions = {

'x0': Condition(location=CartesianDomain({'x': 0.}), equation=FixedValue(1)), # We fix initial condition to value 1

'D': Condition(location=CartesianDomain({'x': [0, 1]}), equation=Equation(ode_equation)), # We wrap the python equation using Equation

}

# sampled points (see below)

input_pts = None

# defining the true solution

def truth_solution(self, pts):

return torch.exp(pts.extract(['x']))

problem = SimpleODE()

After we define the Problem class, we need to write different class

methods, where each method is a function returning a residual. These

functions are the ones minimized during PINN optimization, given the

initial conditions. For example, in the domain \([0,1]\), the ODE

equation (ode_equation) must be satisfied. We represent this by

returning the difference between subtracting the variable u from its

gradient (the residual), which we hope to minimize to 0. This is done

for all conditions. Notice that we do not pass directly a python

function, but an Equation object, which is initialized with the

python function. This is done so that all the computations and

internal checks are done inside PINA.

Once we have defined the function, we need to tell the neural network

where these methods are to be applied. To do so, we use the

Condition class. In the Condition class, we pass the location

points and the equation we want minimized on those points (other

possibilities are allowed, see the documentation for reference).

Finally, it’s possible to define a truth_solution function, which

can be useful if we want to plot the results and see how the real

solution compares to the expected (true) solution. Notice that the

truth_solution function is a method of the PINN class, but it is

not mandatory for problem definition.

Generate data#

Data for training can come in form of direct numerical simulation

results, or points in the domains. In case we perform unsupervised

learning, we just need the collocation points for training, i.e. points

where we want to evaluate the neural network. Sampling point in PINA

is very easy, here we show three examples using the

.discretise_domain method of the AbstractProblem class.

# sampling 20 points in [0, 1] through discretization in all locations

problem.discretise_domain(n=20, mode='grid', variables=['x'], locations='all')

# sampling 20 points in (0, 1) through latin hypercube sampling in D, and 1 point in x0

problem.discretise_domain(n=20, mode='latin', variables=['x'], locations=['D'])

problem.discretise_domain(n=1, mode='random', variables=['x'], locations=['x0'])

# sampling 20 points in (0, 1) randomly

problem.discretise_domain(n=20, mode='random', variables=['x'])

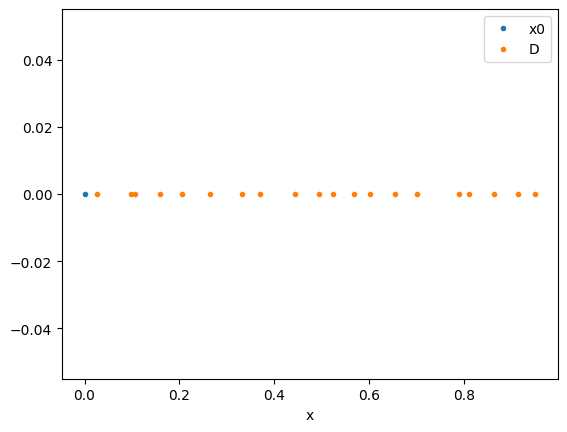

We are going to use latin hypercube points for sampling. We need to

sample in all the conditions domains. In our case we sample in D and

x0.

# sampling for training

problem.discretise_domain(1, 'random', locations=['x0'])

problem.discretise_domain(20, 'lh', locations=['D'])

The points are saved in a python dict, and can be accessed by

calling the attribute input_pts of the problem

print('Input points:', problem.input_pts)

print('Input points labels:', problem.input_pts['D'].labels)

Input points: {'x0': LabelTensor([[[0.]]]), 'D': LabelTensor([[[0.7644]],

[[0.2028]],

[[0.1789]],

[[0.4294]],

[[0.3239]],

[[0.6531]],

[[0.1406]],

[[0.6062]],

[[0.4969]],

[[0.7429]],

[[0.8681]],

[[0.3800]],

[[0.5357]],

[[0.0152]],

[[0.9679]],

[[0.8101]],

[[0.0662]],

[[0.9095]],

[[0.2503]],

[[0.5580]]])}

Input points labels: ['x']

To visualize the sampled points we can use the .plot_samples method

of the Plotter class

from pina import Plotter

pl = Plotter()

pl.plot_samples(problem=problem)

Perform a small training#

Once we have defined the problem and generated the data we can start the

modelling. Here we will choose a FeedForward neural network

available in pina.model, and we will train using the PINN solver

from pina.solvers. We highlight that this training is fairly simple,

for more advanced stuff consider the tutorials in the Physics Informed

Neural Networks section of Tutorials. For training we use the

Trainer class from pina.trainer. Here we show a very short

training and some method for plotting the results. Notice that by

default all relevant metrics (e.g. MSE error during training) are going

to be tracked using a lightining logger, by default CSVLogger.

If you want to track the metric by yourself without a logger, use

pina.callbacks.MetricTracker.

from pina import Trainer

from pina.solvers import PINN

from pina.model import FeedForward

from pina.callbacks import MetricTracker

# build the model

model = FeedForward(

layers=[10, 10],

func=torch.nn.Tanh,

output_dimensions=len(problem.output_variables),

input_dimensions=len(problem.input_variables)

)

# create the PINN object

pinn = PINN(problem, model)

# create the trainer

trainer = Trainer(solver=pinn, max_epochs=1500, callbacks=[MetricTracker()], accelerator='cpu', enable_model_summary=False) # we train on CPU and avoid model summary at beginning of training (optional)

# train

trainer.train()

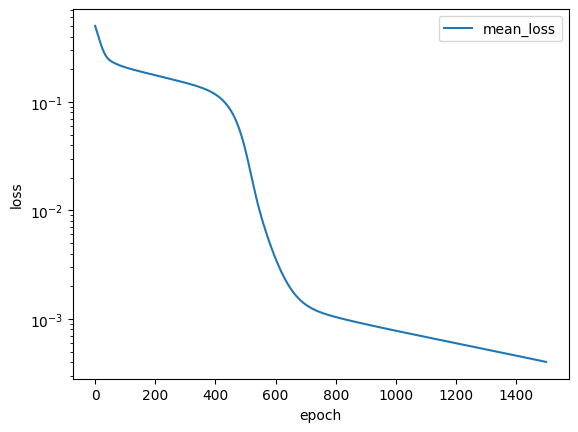

After the training we can inspect trainer logged metrics (by default

PINA logs mean square error residual loss). The logged metrics can

be accessed online using one of the Lightinig loggers. The final

loss can be accessed by trainer.logged_metrics

# inspecting final loss

trainer.logged_metrics

{'x0_loss': tensor(1.0674e-05),

'D_loss': tensor(0.0008),

'mean_loss': tensor(0.0004)}

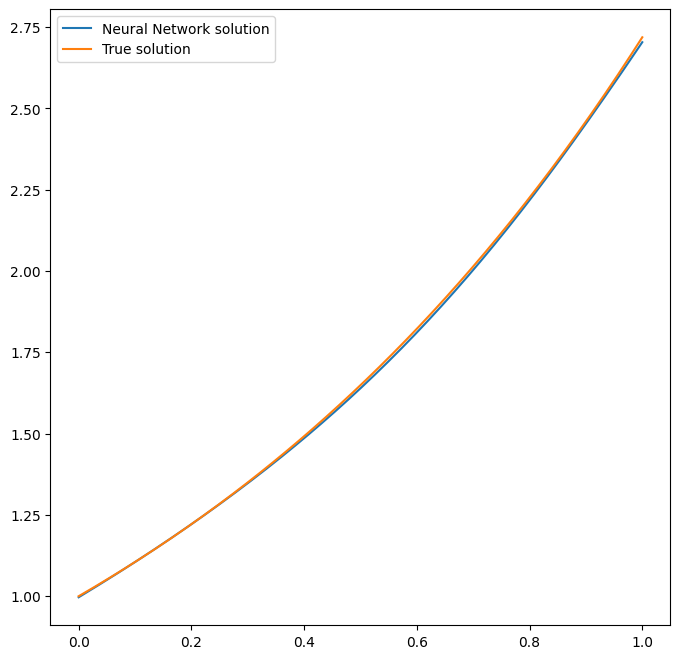

By using the Plotter class from PINA we can also do some

quatitative plots of the solution.

# plotting the solution

pl.plot(solver=pinn)

<Figure size 640x480 with 0 Axes>

The solution is overlapped with the actual one, and they are barely indistinguishable. We can also plot easily the loss:

pl.plot_loss(trainer=trainer, label = 'mean_loss', logy=True)

As we can see the loss has not reached a minimum, suggesting that we could train for longer

What’s next?#

Congratulations on completing the introductory tutorial of PINA! There are several directions you can go now:

Train the network for longer or with different layer sizes and assert the finaly accuracy

Train the network using other types of models (see

pina.model)GPU training and speed benchmarking

Many more…